Despite extensive military assistance to Ukraine, transfers of two sorts of military hardware have remained taboo for Ukraine’s allies: modern Western-designed jet fighters, and long range land-attack missiles.

But as of today, you’ll be able to scratch the second off the list. On Thursday morning, British defense secretary Ben Wallace told the House of Commons that the U.K. had broken the long-range taboo by transferring “a number” of Storm Shadow air-launched cruise missiles, seen as a “proportionate response” to Russia’s sustained air attacks on civilian targets in Ukraine. Storm Shadow is officially advertised as having a spread “exceeding 250km,” or 155 miles, with other figures (including some given by the president of France) suggesting it has a maximum range of 250, and even 350, miles.

It’s unclear whether Ukraine has received fully capable Storm Shadows, or a reduced range model in order to stick to the MTCR arms control regime, which ordinarily discouraged export of missiles with a spread exceeding 190 miles.

While not fast like Russia’s Kinzhal aerial ballistic missile, the five-meter-long Storm Shadow is noted for its high degree of stealth, AI-driven image-matching terminal guidance system, and bunker-busting two-stage warhead (as further detailed below). Since it’s entirely pre-programmed for its targets prior to takeoff, it ought to be easier to integrate onto Ukraine’s Soviet warplanes than other advanced Western guided weapons.

Western governments feared Ukraine might use long-range missiles for attacks on Russian soil deemed politically provocative, which could incite escalatory retaliation. That, together with limited inventory, has most notably kept the U.S. from donating 190-mile range ATACMS ballistic missiles which might be ordinarily compatible with the HIMARS and M270 rocket artillery systems donated to Ukraine.

Wallace stated that the Storm Shadows were supplied with assurances from Ukraine that they might only be used for strikes on Russian-occupied parts of the country, similar to logistical centers in Starobilsk and Melitopol.

But the true bullseye falls on Russia’s extensive military infrastructure on the Crimean Peninsula, including airbases and far of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet. Russia had leased bases in that area from Ukraine for twenty years, just for Putin to invade your complete peninsula in 2014.

The politics of Donated Missiles

Provided that the donation from the UK feels like it was in limited quantity (“a number”), the UK’s Storm Shadow may effectively be more a political play than a military one, very like when the country donated Western-designed primary battle tanks.

Though the latter quantity was relatively small—14 Challenger 2 tanks—it may have helped end hesitation for much larger subsequent donations of Leopard 2 and M1 tanks from the U.S. and continental Europe. The UK has been less concerned by the ‘but how will Putin react?’ factor than France or Germany.

Fortunately for Ukraine, Storm Shadow donations usually tend to be scalable than the UK’s rare Challenger 2 tanks, because the missiles are also in France’s inventory—under the designation SCALP-EG—and Italy’s. Each are major donors to Ukraine. The French Navy also uses a longer-range ship-launched variant called the MdCn.

Western governments might see whether Middle Eastern Storm Shadow clients (Egypt, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the UAE) are amenable to quietly selling back missiles in exchange for newly-built replacements later. Those sold to the Middle East are believed to be a downgraded variant with 180-mile range sometimes dubbed the Black Shaheen—still potentially useful for Ukraine’s purposes.

Origins of Storm Shadow

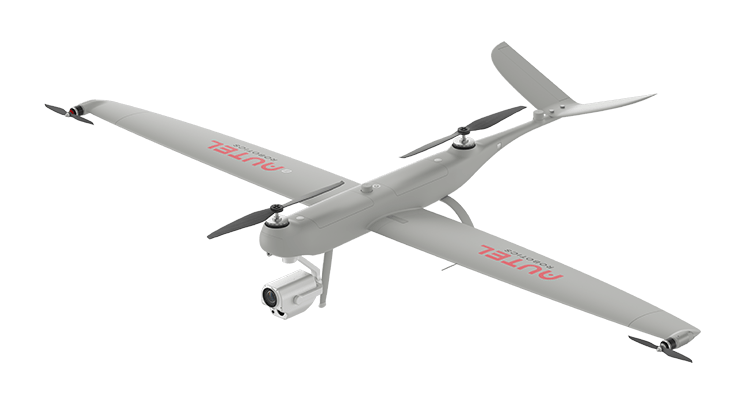

To not be confused with the G.I. Joe villain of the identical name, Storm Shadow/SCALP is a French-U.K. three way partnership built by European missile-maker MBDA and based on the Apache runway-cratering missile. It and Germany’s KEPD-350 air-launched cruise missile are essentially the most quite a few European-built equivalents to the U.S.’s arsenal of Tomahawk land-attack missiles, which have for much longer range and are primarily (but not exclusively) sea-launched.

Storm Shadow doesn’t use any input from the carrying aircraft before or after launch. As an alternative, it’s pre-programmed on the bottom to follow waypoints to the goal area autonomously using inertial and GPS navigation—normally skimming at just 100-130 feet above the bottom to further reduce radar detectability. Supported by pop-out wings, it flies slightly below the speed of sound powered by small TRI 60-30 turbojet engine and boasts a low radar-cross section as a consequence of its non-reflective geometry.

This content is imported from youTube. Chances are you’ll have the opportunity to seek out the identical content in one other format, or you might have the opportunity to seek out more information, at their website online.

Once near the goal, the missile lunges upwards–tossing off its pointy nose cone and exposing the infrared sensor inside—and uses its elevated vantage to scan the bottom below, looking for anything that resembles preloaded satellite images of the goal using an early AI-driven technology called DSMAC (Digital Scene Matching Area Correlator.)

If the missile can’t find the goal, it could possibly be assigned a crash point in order to not risk collateral damage. But on finding a match, it swoops down and, just before impact, discharges the pre-cursor charge of its nearly half-ton (992-pound) BROACH warhead.

The armor-penetrating precursor blasts a hole into the goal’s surface, allowing the larger primary charge to pass contained in the targeted structure before detonating—making BROACH effective against hardened targets like underground storage facilities and bunkers.

And while a Storm Shadow can go further and has a much larger warhead than a GMRL rocket, it’s also 4-5 times costlier, so Ukraine will receive a much smaller number. Which means each shot can have to count, and there won’t be an indefinite resupply of missiles, making avoiding interception much more pertinent.

Storm Shadow was first utilized in combat throughout the 2003 invasion of Iraq by now-retired British Tornado jets. France’s SCALP-EG missiles followed in 2011, deployed by Mirage 2000Ds and carrier-based Rafale-M jets within the campaign to overthrow Qaddafi in Libya. Within the mid-2010s, the UK and France also employed the missiles against ISIS in Iraq and Syria, and in strikes punishing the Syrian government for its use of chemical weapons.

Western Missiles on Soviet Warbirds

Storm Shadow/SCALP is designed to be lofted from aircraft, and has been integrated into Sweden’s JAS-39 Gripen fighter, France’s Mirage 2000 and newer Rafale fighters, and Tornado jets and newer Eurofighter Typhoons built by Germany, Italy, and the UK.

But because Storm Shadows don’t require fire control instructions from the launching fighter, they ought to be comparatively easy so as to add onto the Ukrainian Air Force’s Soviet warplanes.

Ukraine has already managed to mount AGM-88 HARM anti-radar missiles on its MiG-29 jets, a modification likely enabled by the actual fact the HARM has a built-in seeker. Resulting from Storm Shadow’s considerable size and weight, it could seek to mount it on large-but-fast Su-24 Fencer bombers or Su-27 fighters.

Resulting from Storm Shadow’s considerable range, Ukrainian jets could release the missile from relatively secure airspace. That said, to delay/avoid detection by Russian ground-based radars and attack from an unpredictable angle, Ukraine may go for launch from low altitude—even when that reduces the utmost range and requires getting closer. There may due to this fact still be some have to dodge patrolling Russian MiG-31 interceptors, and Su-35 fighters scanning from above and primed to launch very-long-range R-37M missile.

Theoretically, Ukraine could also cobble together means to ground-launch Storm Shadows, accepting a significantly reduced range.

Like most long-range cruise missiles, Storm Shadows will not be low cost—probably costing around $1 million per shot. And most operators have inventories within the low-to-mid lots of, not 1000’s, limiting what number of they’re inclined to donate. Still, if the UK’s donations breaks the taboo on transferring long-range missiles to Ukraine, then multiple donors may help make up numbers—to an extent.

Long-range Strike Tactics

When, in the summertime of 2022, Ukraine began using Western-supplied HIMAR systems to launch GMLR precision-guided rockets out to a spread of 56 miles, it resulted in a succession of spectacularly destructive attacks on Russian HQs, airbases, and ammo depots.

Those spectacles declined in frequency after just a few months, because the Russians learned their lesson and pushed vulnerable support structures back outside of HIMARS range—accepting a lack of efficiency for higher survival odds. Russia also began employing GPS-jamming to throw off the aim of HIMARS and SDB glide bombs given to Ukraine.

In theory, then, Storm Shadow and similar weapons could give Ukrainian planners a second “comfortable period,” as Russian depots and HQs again fall into convenient precision-strike range—potentially devastating if timed to coincide with Ukraine’s anticipated 2023 counteroffensive.

And this time, those depots and command centers may need to relocate all of the option to Russian soil to flee the Storm Shadow’s reach. That would especially threaten Russian forces in southern Ukraine, most distant from the Russian border.

But there are necessary differences to take into account. While Russian air defenses struggled to shoot down supersonic HIMARS rockets, Storm Shadow is a subsonic cruise missile—a category of weapon that Ukraine’s own air defense system has turn out to be efficient at shooting down.

Storm Shadow’s success—versus Russia’s technically superior air defenses—will depend partially on its stealth characteristics. Since the missile relies on image-matching as a substitute of GPS for terminal guidance, it should not less than be less degraded by Russian GPS jamming than HIMARS rockets.

Mena Adel, who writes on military aviation for Scramble magazine, told Popular Mechanics that tactics practiced by France and the UK using SCALP/Storm Shadow against Syria’s Soviet-built air defense systems offer a relevant model for Ukraine:

“The U.S., France and UK attacked with a sweeping attack by 4 several types of missiles, including [non-stealth] Tomahawk missiles which formed the most important part to disperse the Syrian air defense thereby reducing the possibility of intercepting stealth missiles. All while monitored by Russian air defenses in Syria… It is definite that future attacks will probably be planned using several types of missile approach from different directions to deceive the Russian systems in order that the specified targets are hit with great accuracy and a minimum interception rate. Stealthiness is just not enough, success will rely upon planning and deception.”

As Ukraine won’t have nearly as many cruise missiles available, Adel suggested Ukraine might as a substitute launch concerted attacks with drones and SDB glide bombs (each ground- and air-launched) supported by electronic warfare systems to confuse and overwhelm Russian air defenses.

Ukraine’s promise to not strike Russian soil with Western-supplied missiles could also encourage a false flag attack making it appear it has done so—a well-established tactic in Putin’s playbook. As Ukraine is sporadically attacking targets in Russia (mainly airbases, oil depots and electrical infrastructure) using agents and domestically-built drones and missiles, there might be grounds for confusion and misinformation.

Overall, Storm Shadow is a potent long-distance strike weapon Ukraine can have to employ judiciously for optimum effect—though even the likely modest number transferred to Ukraine will prone to cause anxiety to Russian logisticians, commanders, and air defense personnel.