ICON

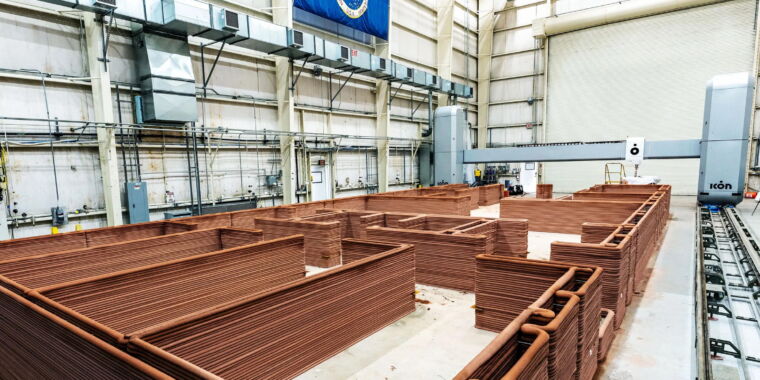

In June a four-person crew will enter a hangar at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas, and spend one yr inside a 3D-printed constructing. Manufactured from a slurry that—before it dried—looked like neatly laid lines of soft-serve ice cream, Mars Dune Alpha has crew quarters, shared living space, and dedicated areas for administering medical care and growing food. The 1,700-square-foot space, which is the colour of Martian soil, was designed by architecture firm BIG-Bjarke Ingels Group and 3D printed by Icon Technology.

Experiments contained in the structure will give attention to the physical and behavioral health challenges people will encounter during long-term residencies in space. But it surely’s also the primary structure built for a NASA mission by the Moon to Mars Planetary Autonomous Construction Technology (MMPACT) team, which is preparing now for the primary construction projects on a planetary body beyond Earth.

When humanity returns to the Moon as a part of NASA’s Artemis program, astronauts will first live in places like an orbiting space station, on a lunar lander, or in inflatable surface habitats. However the MMPACT team is preparing for the development of sustainable, long-lasting structures. To avoid the high cost of shipping material from Earth, which might require massive rockets and fuel expenditures, which means using the regolith that’s already there, turning it right into a paste that will be 3D printed into thin layers or different shapes.

The team’s first off-planet project is tentatively scheduled for late 2027. For that mission, a robotic arm with an excavator, which shall be attached to the side of a lunar lander, will sort and stack regolith, says principal investigator Corky Clinton. Subsequent missions will give attention to using semiautonomous excavators and other machines to construct living quarters, roads, greenhouses, power plants, and blast shields that may surround rocket launch pads.

Step one toward 3D printing on the Moon will involve using lasers or microwaves to melt regolith, says MMPACT team lead Jennifer Edmunson. Then it must cool to permit gases to flee; failure to accomplish that can leave the fabric riddled with holes like a sponge. The fabric can then be printed into desired shapes. The best way to assemble finished pieces continues to be being decided. To maintain astronauts out of harm’s way, Edmunson says the goal is to make construction as autonomous as possible, but she adds, “I can’t rule out the usage of humans to take care of and repair our full-scale equipment in the longer term.”

One among the challenges the team faces now could be the best way to make the lunar regolith right into a constructing material strong enough and sturdy enough to guard human life. For one thing, since future Artemis missions shall be near the Moon’s south pole, the regolith could contain ice. And for an additional, it’s not as if NASA has mounds of real moon dust and rocks to experiment with—just samples from the Apollo 16 mission.

So the MMPACT team has to make their very own synthetic versions.

Edmunson keeps buckets in her office of a couple of dozen mixtures of what NASA expects to search out on the Moon. The recipes include various mixtures of basalt, calcium, iron, magnesium, and a mineral named anorthite that doesn’t occur naturally on Earth. Edmunson suspects that white and glossy synthetic anorthite being developed in collaboration with the Colorado School of Mining is representative of what NASA expects to search out on the lunar crust.

Yet while the team feels that they will do a “reasonably good job” of matching the geo properties of the regolith, says Clinton, “it’s extremely hard to make the geo properties, the form of the several tiny pieces of aggregate, because they’re built up by collisions with meteorites and whatever has hit the Moon over 4 billion years.”

There are other X aspects to account for when constructing on the Moon—and quite a bit can go improper. Gravity is far weaker, there’s a likelihood of moonquakes that may create vibrations for as much as 45 minutes, and temperatures on the south pole can get as high as 130° Fahrenheit in sunlight and as little as –400° at night. Abrasive moon dust can clog machinery joints and convey hardware to a screeching halt. Throughout the Apollo missions, regolith damaged space suits, and inhaling dust caused astronauts to experience hay-fever-like symptoms.

Constructing Mars Dune Alpha, the test habitat in Texas, had a good larger X factor: The human race has never brought a sample of Martian soil back to Earth, so Icon needed to simulate the fabric, based on predictions of what it’s made out of—reminiscent of that it’s wealthy in basalt. (They call their constructing material “lavacrete.”) An important part to NASA officials, says CEO Jason Ballard, was getting the Martian soil’s color match right, to accurately mimic what it could be prefer to continue to exist the red planet.