A truck-mounted, multiple-barrel rocket launcher can send 48 missiles flying toward a goal all in a minute. Such a launcher is extremely mobile, very fast, relatively low cost, and straightforward to operate. No wonder a weapon like that’s popular in conflict regions.

However the launcher’s questionable quality could cause the missiles to often misfire, which is why they often litter the bottom in targeted areas. The issue, then, is finding them. Now scientists think they’ve the tech to simply track and retrieve them.

Finally month’s American Geophysical Union Annual Meeting in San Francisco, researchers reported a brand new technique to discover these unexploded ordnances, or UXO, from the air. Using hybrid drones and shrunken technology, the scientists can survey as much as 100 acres an hour and have a map of possible armaments inside minutes.

“There’s this type of evolutionary moment when the 2 technologies are meeting for the primary time—the miniaturization of sensors and the dependability of drones,” says lead study creator Alex Nikulin, a geophysicist and Binghamton University professor. “The union of those two things changes the sport.”

(Un)Explosions Galore

Truck-launched missiles spray across a 600-meter-wide area, says Nikulin, in comparison with a single location. And the targets move. “For instance, if you’ve got a checkpoint that’s in a single place this week, next week it’s someplace else,” he says.

Shelling will be almost continuous, but not every missile explodes. Out of this barrage, Nikulin says anywhere from 20 to 40 percent (and as high as 80 percent, depending on the standard of the missile) of the explosives can fail to detonate.

“Different countries make higher or lower quality ordnances,” says the study’s coauthor, Timothy de Smet, also a geophysicist and professor at Binghamton. He says some fighters get knockoff missiles or raid stockpiles that will be greater than 30 years old—and explosion rates can plummet because the missiles wear down with time.

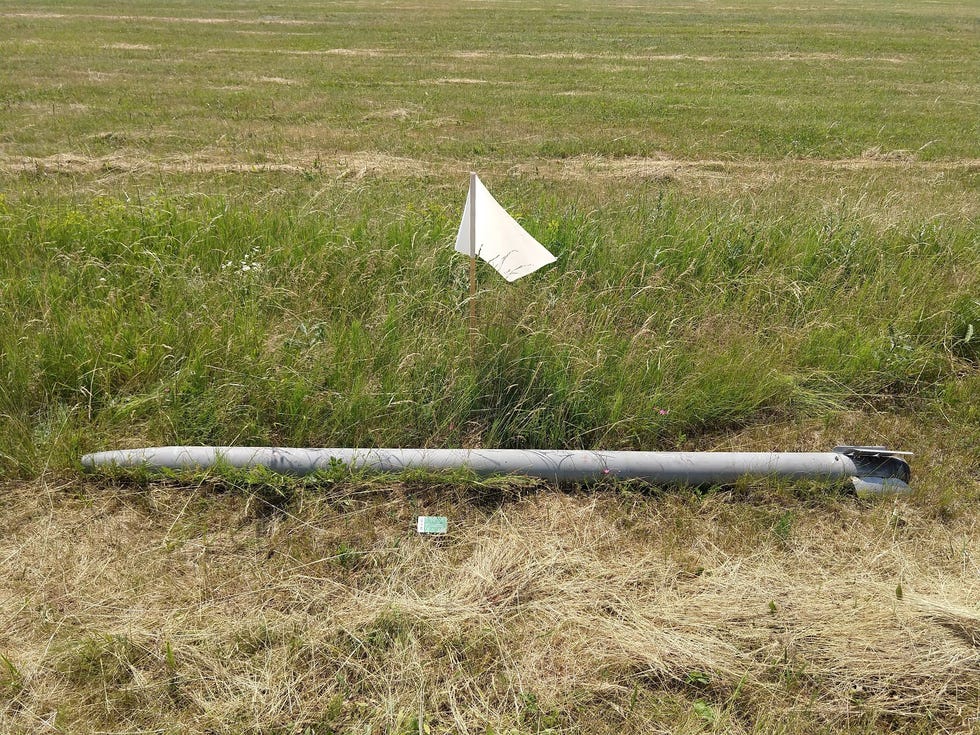

The result? Post-conflict landscapes will be chock stuffed with hazardous, 3-meter-long unexploded missiles.

Hybrid Drones

Although people can find errant missiles, the duty is lower than ideal. On-foot surveys can take an extended time and the risks are high. Drone surveys can remove the human element and reduce risk.

But drone flights are notoriously short, making surveys difficult. “The massive problem we bumped into was once we began this was battery life,” says Nikulin. He notes that prior drones—from inexpensive to premium—had short, 15- to 20-minute flight times. “We will’t use those drones for wide service areas.”

Enter the Ukrainian company UMT, which developed a hybrid drone called Cicada that may stay within the air for 3 hours. Nikulin says they read concerning the latest drone, wrote the corporate, and ended up collaborating on the brand new study with the UMT engineers to seek out UXO.

“Geophysical methods will be very effective for UXO detection,” says Andrei Swidinsky, a geophysicist at Colorado School of Mines who wasn’t involved within the study. “Several methods operate in principles much like airport metal detectors, and as such are sensitive to UXO which may be present in post-conflict zones.”

Needle within the Haystack

In an airfield in Ukraine, the scientists tested how a drone-carried microfabricated magnetometer might detect 3-meter-long missiles. UMT flew the Cicada over the sector with the magnetometer dangling below.

“A significant challenge [in geophysical surveys] is to categorise and discriminate UXO from background clutter (scrap metal etc.), to stop unnecessary remediation efforts,” says Swidinsky.

But knowing their goal shape and signature allowed the researchers to leverage the sensor capabilities to get the right picture of what is perhaps buried underground. “You should use the altitude to filter out clutter,” says de Smet.

Objects lose their magnetic signal quickly with distance, he says, so there’s a sweet spot for locating a 3-meter missile. “All the pieces that’s smaller than the item you’re searching for disappears,” says de Smet. “You’re using the altitude as a low-pass filter.”

The long flight time, paired with keyed-in elevation, meant the time got a map of the ordnances in brief order—a complete field of information inside 45 minutes. Nikulin says he and his team want their technique to be usable on the bottom. “Our entire idea is you principally open up a laptop and in five minutes you’ve got an actionable map.”

With the magnetometer, each UXO is geolocated using GPS, allowing researchers to plot locations on a map. Through the survey, the team found an ordnance that was unknown to the Ukraine military. The missile was buried vertically, with only the very tail end peaking above the soil. With a handheld GPS, the team walked out to the placement with the military personnel and located the almost-hidden ordnance. “At that time, their faces just went white,” says Nikulin.

Tools of the Trade

For the reason that field test, the team has been certified for IMAS, or the International Mine Motion Standards Certification. The scientists’ method is now certified for a large area technical survey, which is basically confirming the absence of presence of a threat. “Then you definately because the stakeholder, the federal government regulator, the emergency ministry, the humanitarian organization, can use that data to plan your work,” says Nikulin.

“Using an autonomous platform allows large areas to be quickly surveyed at low price, and minimal risk to operators,” says Swidinsky. He notes that drone-based geophysics has moved past experimental stages and is now a routine approach.

As for locating UXO, Nikulin says this so far as the scientists can go. “Now,” de Smet echoes, “we hand it over to non-governmental organizations.”