WASHINGTON — NASA chosen Blue Origin to develop a second Artemis lunar lander due to technical strengths corresponding to an aggressive schedule of test flights in addition to its lower cost.

In a source selection statement published shortly after NASA announced it picked Blue Origin for the Sustaining Lunar Development (SLD) award May 19, the agency explained the way it chosen that company’s proposal over a competing bid by Dynetics.

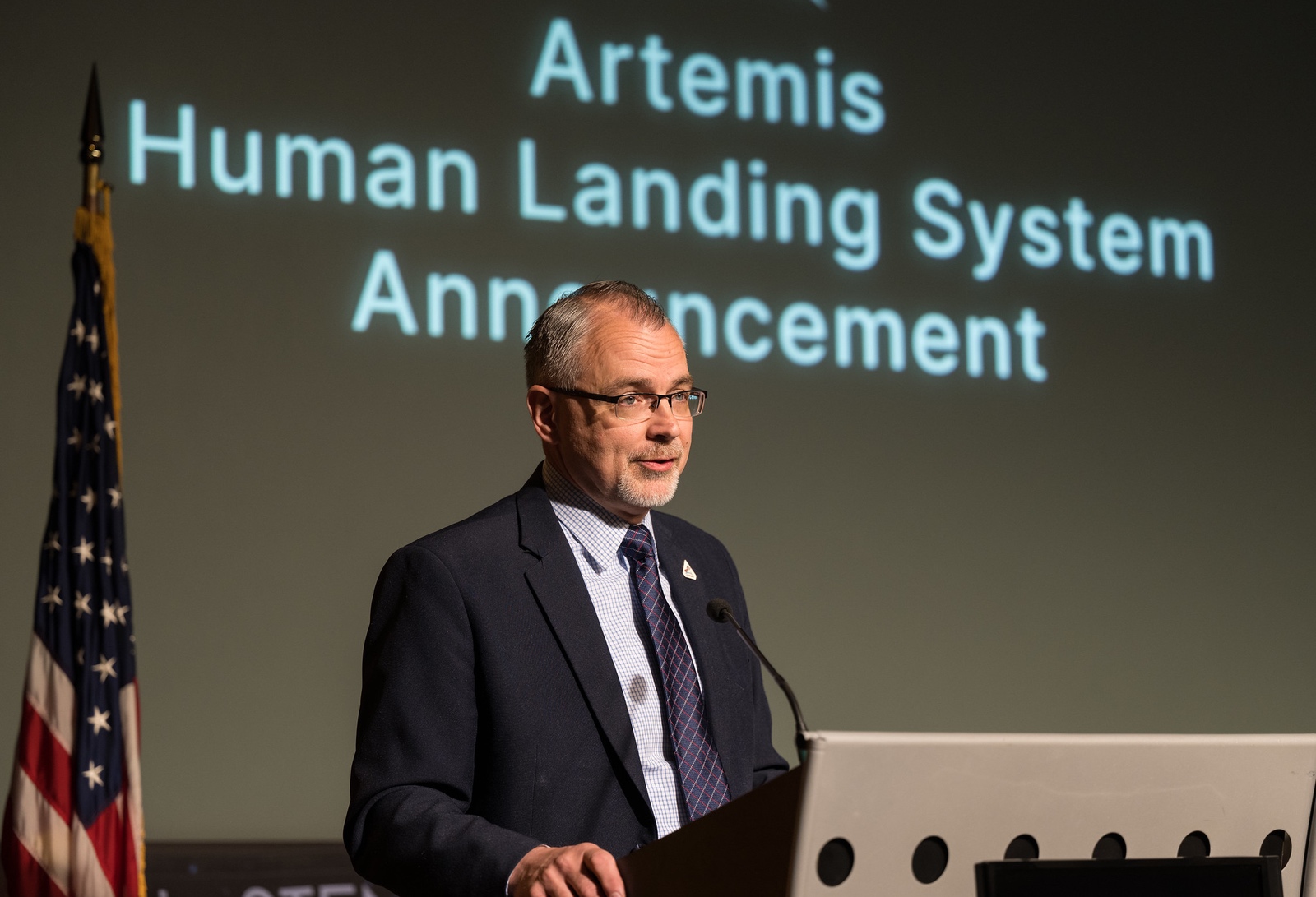

Jim Free, NASA associate administrator for exploration systems development, served because the source selection official for the competition and wrote within the statement that he agreed with the agency’s evaluation of the proposals. “This evaluation leads me to the conclusion that Blue Origin’s proposal is essentially the most advantageous to the Agency across all evaluation aspects, and it aligns with the objectives of the solicitation,” he wrote within the statement, signed May 8.

Several facets of Blue Origin’s proposal for its Blue Moon lander stood out to him. Amongst them was Blue Origin’s plans for a series of missions to check its lander technology before the required uncrewed test flight of the lander. The statement specifically mentions “pathfinder lander missions” in 2024 and 2025 that might mature key elements that currently have low technology readiness levels (TRLs) before the uncrewed test.

“I find this aspect of the proposal to be compelling — it’s a forward-thinking solution to mature key low-TRL technologies allowing for incorporation for any changes into the ultimate design,” Free wrote. He added that “there is no such thing as a financial impact to NASA since the pathfinder missions are being funded by Blue Origin.”

The statement doesn’t mention which technologies can be demonstrated on those pathfinder missions. Through the NASA briefing, John Couluris, Blue Origin program manager, said the corporate planned “plenty of test launches and landings,” details of which can be disclosed later.

Those would involve a “Mark 1” version of the lander “to prove technologies for these future landers, before crew members even step inside,” he said. Blue Moon wouldn’t carry people until the Artemis 5 mission.

Before Artemis 5, Blue Origin will perform an uncrewed landing with the identical version of the lander that can carry people. Free noted that while NASA only required corporations to perform a landing for the Uncrewed Flight Test (UFT) that demonstrated precision landing capabilities, Blue Origin is carrying out a full test of the lander, including life support systems, and the flexibility to launch back to the near-rectilinear halo orbit.

“I find that using a completely matured crewed lander configuration for the UFT is one other compelling aspect of the technical proposal — it’s a major strength that is very advantageous to NASA because it’s going to decrease risk to the crewed demonstration mission,” he wrote.

The source selection statement also identified as significant strengths within the proposal “excess capabilities” within the lander that allow it to perform additional missions, in addition to a business approach that features a significant investment and “a powerful commitment to future cost reductions.” Couluris said on the briefing that the corporate would contribute significantly more to the event of Blue Moon than NASA’s $3.4 billion.

Nonetheless, NASA did discover two weaknesses in Blue Origin’s proposal. One involves its communications system, which had a risk of not meeting agency requirements for continuous communications. The opposite is the corporate’s Integrated Master Schedule, which Free wrote “comprises quite a few conflicts and omissions.”

The Dynetics proposal won strengths for offering excess capabilities, like Blue Origin, for other classes of landing missions, and for a business approach that envisions other customers and missions for its lander architecture. “Dynetics’ business approach is flexible within the concepts presented and aligns with continuing to construct the business space economy,” Free stated.

NASA, though, raised concerns about whether the Dynetics lander would meet all the necessities, noting some confusion between two different landers mentioned within the proposal. “I’m highly concerned with this proposed approach and consider these flaws to be a major weakness because I’m unclear which capabilities will likely be demonstrated on the CDM,” or Crew Demonstration Mission, Free wrote, citing it as a major weakness.

One other significant weakness is that Dynetics proposed maturing eight major technologies on a single test flight in 2027, nine months before the review for the CDM. That approach, he warned, “allows little or no opportunity to affect the CDM lander construct and operation should the necessity for design or operational changes arise while maintaining schedule.”

The statement didn’t disclose the worth Dynetics offered for the lander, however the statement noted it was “substantially higher” than Blue Origin’s proposal.

In an announcement to SpaceNews, Dynetics and its parent company, Leidos, appeared to just accept the consequence of the competition and showed no sign it will file a protest. Each Blue Origin and Dynetics had protested the number of SpaceX for the unique Human Landing System award, but had that rejected by the Government Accountability Office.

“Helping NASA with the inspiring efforts to return to the moon will remain a priority for Leidos. The Artemis missions require multiple partners to realize success, and our Leidos-Dynetics team is committed to continuing to help on these critical missions,” the corporate said, citing work on several projects and plans to bid on a Lunar Terrain Vehicle rover for later Artemis missions.