Servicing satellites in orbit is a nascent segment of the space economy that the U.S. military has been watching mostly from the sidelines.

The Space Force says it’s now able to get in the sport. It’s investing in early-stage technologies and laying out a technique to purchase business services to refuel and repair satellites in geostationary orbit by the early 2030s.

The military’s fascinated about satellite servicing has modified from just just a few years ago when space operators didn’t see a robust use case for in-orbit repairs and refueling. Now it’s viewed as a strategic advantage, said Vice Chief of Space Operations Gen. David Thompson.

The Space Force considers satellite servicing and in-orbit logistics as “core capabilities” and is watching developments within the business industry, said Thompson.

“We’re able to use the technology as soon because the market is there,” he said May 15 at a Space Force Association event. Meanwhile, “there’s an entire bunch of design and evaluation we’ve got to do to work out what is sensible.”

Congress signaled support for these efforts, inserting $30 million within the 2023 Space Force budget for on-orbit servicing technologies. Thompson last 12 months directed the Space Systems Command to make use of the funds to determine a program office and work out a procurement strategy for satellite servicing.

The brand new office is just beginning to get off the bottom, said Maj. Gen. Stephen Purdy, program executive officer for assured access to space on the Space Systems Command.

Purdy said military space operators are sending a transparent demand signal for in-orbit capabilities, and the goal is to create a dedicated budget line for these services.

“It’s somewhat little bit of the classic starter’s dilemma,” he told , noting that starting recent programs within the Defense Department is notoriously cumbersome. Meanwhile, “there’s a desire to have a refueling capability.”

‘We want logistics’

A powerful case for satellite refueling has been laid out by Lt. Gen. John Shaw, deputy commander of U.S. Space Command. At recent industry events, Shaw argued that the way in which DoD has acquired satellites for many years — with out a capability to refuel in orbit — prevents operators from freely maneuvering spacecraft in response to threats.

Shaw compared it to purchasing a automobile with a single tank of fuel and having to make it last for your entire lifetime of the vehicle.

“We want to have on-orbit logistics and repair capabilities,” Shaw said in a speech on the Space Symposium in April.

Space Command, for instance, operates “neighborhood watch” satellites generally known as GSSAP (Geosynchronous Space Situational Awareness Program) to watch the geostationary belt, where the military deploys its most respected assets. GSSAPs were built to last for many years, but maneuvers should be rigorously planned to attenuate fuel consumption.

“If I had the power to refuel GSSAP usually, do you’re thinking that we’d operate them like we do today? We might not,” Shaw said. “We can be zipping across the globe. We’d be attempting to keep a possible adversary off balance.”

Purdy said that message has been heard loud and clear.

“We cannot do warfighting within the space domain if we’ve got to measure every drop of fuel and choose whether you actually need to do that mission if meaning the satellite will run out of fuel two years early,” he said.

Projects within the works

Purdy assigned Col. Meredith Beg to steer the brand new Space Force office focused on space mobility and logistics.

“Our goal is to be sure that we will deliver this capability that the combatant command is clamoring for,” Beg told .

“We don’t have an outlined budget yet. But we’re working through the company process to determine what that should appear like,” she said.

Satellite servicing is a component of the broader activity generally known as ISAM, for in-space servicing, assembly and manufacturing. The Space Force is eager about ISAM, but its major focus is mobility and maneuver, said Beg. Refueling is the “near-term requirement.”

These technologies are also being pursued by Space Force under the Orbital Prime program aimed toward small businesses. Launched in 2021, Orbital Prime has awarded about 125 research and study contracts to groups of industry and academia.

Outside the Space Force, other organizations funding in-orbit satellite servicing programs include the Air Force Research Laboratory and the Defense Innovation Unit. But probably the most significant investment today is coming from the private sector, Beg noted. “We’re seeking to leverage all that onerous work and brainpower to really deliver capabilities to our warfighters.”

Of the $30 million Congress added in 2023, $26 million can be allocated to projects managed by the Space Enterprise Consortium, a Space Systems Command organization that works with startups and business space firms.

In June, the SpEC consortium plans to request prototype proposals “to support the event of a strong business base able to providing space mobility and logistics services.”

SpEC, in a draft solicitation, noted that few business services can be found. “Nonetheless, multiple performers are working towards technology demonstration.”

Proposals are sought in 4 areas: refueling, transportation, servicing and debris mitigation.

The SpEC plans to award a number of contracts for projects that can be co-funded by the $26 million appropriated within the Space Force budget and $7.8 million from the winning contractors. Developing technologies under private-public partnerships allows the Space Force to influence business technology development.

Refueling demonstration planned

Beg said a long-term acquisition strategy for refueling and other in-orbit services remains to be to be mapped out.

To assist inform the procurement strategy for in-orbit refueling, the Space Force is funding experiments comparable to the $50 million Tetra-5, co-sponsored by the Defense Innovation Unit.

The Space Systems Command’s Innovation and Prototyping Directorate last summer awarded Orion Space Solutions a contract to develop three small satellites that may dock with a hydrazine depot in geostationary orbit supplied by the business startup Orbit Fab. The experiment is projected to launch in 2025.

The top of the prototyping directorate, Col. Joseph Roth, said the Tetra-5 experiment, if successful, will help construct confidence within the technology.

“Colonel Beg and the remaining of us are getting really strong signals from the warfighting units that they wish to have on-orbit refueling capability and logistics,” said Roth. “It should take time to determine requirements and put within the budget, but it surely’s pretty exciting to see.”

DARPA pioneered in-orbit servicing

For years, Josh Davis, senior project engineer on the Aerospace Corp., has studied developments in space mobility and logistics.

The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) in 2007 demonstrated in-orbit refueling in an experiment called Orbital Express. Although the project was successful, Davis noted, the military never transitioned the technology to an operational program because there was no actual need for it.

The Air Force operated satellites in space for greater than 50 years without refueling or in-space logistics capabilities, Davis said. Now that a necessity has been identified, the Space Force has to work through the Pentagon’s requirements process. “From a budgeting perspective, it’s very hard to get up a brand new mission area,” he said.

Transitioning to a satellite fleet that may be serviced in orbit, he said, also requires constructing next-generation spacecraft equipped with refueling ports compatible with available servicing vehicles.

The excellent news for the Space Force, Davis said, is that the industry has advanced rapidly since Orbital Express. There are actually business corporations capable of provide services, so the federal government doesn’t need to construct unique systems.

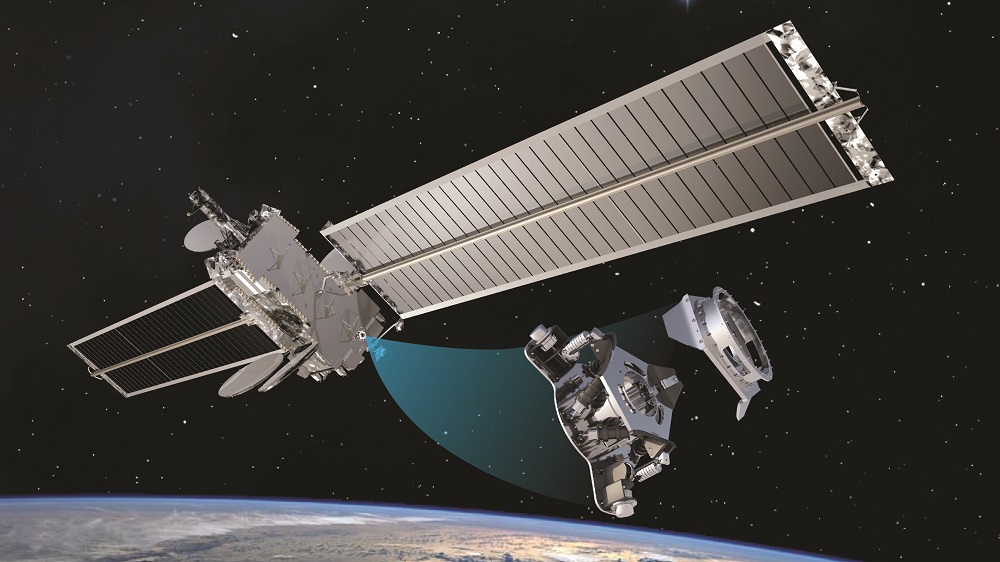

DARPA, in 2020, signed an agreement to share its satellite servicing technology with a business firm, Northrop Grumman’s SpaceLogistics. The corporate now has two Mission Extension Vehicles in orbit docked with two Intelsat geostationary satellites that were running low on fuel, and can keep those satellites in service for about 15 years.

Satellite operators Intelsat and Optus have ordered two of three fuel pods to be delivered by SpaceLogistics’ recent Mission Robotic Vehicle, projected to launch in 2024 to increase the lifetime of geostationary satellites by a minimum of six years. The third customer has not yet been announced.

Despite uncertainty about DoD funding for satellite servicing, the industry is making investments in anticipation of presidency demand, Davis said.

He pointed to Shaw’s comments as a “very clear demand signal from the Space Force’s customer, U.S. Space Command.”

Standard interfaces for spacecraft

For the satellite servicing industry to take off, Davis said, decisions can have to be made about hardware and software interfaces to make vehicles interoperable.

“As we move forward, there is unquestionably a variety of interest in determining how we standardize the servicing features on our next generation of satellites,” he said.

Volumes of standards have been developed for NASA programs comparable to the International Space Station, but those should not applicable to military satellites.

The Space Force has a variety of work to do on this area, Davis said. It’s unlikely that the industry will adopt the equivalent of a USB plug-and-play standard for spacecraft, a minimum of within the foreseeable future, Davis added. “Eventually, I’d like to get there.”

Firms like Northrop Grumman, Lockheed Martin, Astroscale, Orbit Fab and others are developing interfaces, and a few could also be more widely adopted than others. “Any individual goes to get the market first, and so they’re going to get the lion’s share,” said Davis.

He noted that the industry group generally known as CONFERS (Consortium for Execution of Rendezvous and Servicing Operations) can have a vital role to play on this area.

CONFERS was founded by DARPA in 2017 to assist develop and promote industry-led standards for satellite servicing activities. The consortium has greater than 50 member organizations from the U.S. and several other other countries.

Roth, the director of prototyping at Space Systems Command, said government and industry experiments will help test different interfaces “to see which works the most effective.”

“We do keep our eye on the economic base,” particularly on satellite refueling developments,” he said. “We’re just on the early stages of on-orbit refueling, and I’m glad we’ve got a strong industrial base that’s actually exploring this for business use.”

Roth said the Space Force is closely watching Northrop Grumman’s servicing vehicles and the corporate’s next-generation mission refueling pods. “We’re definitely going after business opportunities,” he said.

Open-source docking device

With a watch on the military satellite servicing market, Lockheed Martin in April 2022 released the technical specifications of a docking device — called Augmentation System Port Interface, or Aspin. Lockheed Martin hopes satellite manufacturers will adopt the usual to be able to make satellites interoperable and easier to update on orbit with recent technology.

“We’re definitely that port,” Roth said. A horny feature of Aspin, he said, is that it was designed to be compatible with Orbit Fab’s refueling port called Rafti — short for rapidly attachable fluid transfer interface.

Lockheed Martin’s vice chairman of mission strategy Eric Brown said the Aspin port was designed to enable a broad range of services, including refueling satellites, recharging batteries or adding recent payloads.

“We’re seeing the demand signals coming from the fitting places, definitely for refueling,” Brown said.

Along with Aspin, the corporate is investing in rendezvous and proximity operations technology. Two Lockheed Martin cubesats conducted an illustration in geostationary orbit in November, performing maneuvers in close proximity.

Within the experiment called Lockheed Martin’s In-space Upgrade Satellite System, or Linuss, one in all the cubesats performed the role of servicing vehicle and the opposite served because the resident space object.

Brown said Lockheed Martin is planning a brand new experiment to check the Aspin docking adapter in space.

“We expect Aspin to be stock content on any satellite that we intend to propose to the U.S. government and allies,” Brown said. “And we expect that each satellite program that the Space Force procures goes to ask for the power to be refueled.”

Lockheed Martin, an investor in Orbit Fab, purposely designed Aspin to be interoperable with the Rafti port. But Aspin also will enable other capabilities comparable to snapping on a brand new processor to a satellite.

One among the concepts envisioned for Aspin is to place the port on a small satellite carrying a brand new processor or sensor that might be launched to orbit and, under its own propulsion, dock with the client satellite.

“The issue we’ve got today is you design these satellites over the course of several years, and technology continues to evolve,” Brown said. Technologies like Aspin would allow the Space Force to update their satellites relatively quickly.

Gas stations in space

Orbit Fab announced plans in 2022 to supply refueling services in geostationary orbit by 2025 at a price of $20 million for 100 kilograms of hydrazine.

The corporate will deploy a depot and “shuttle” spacecraft to take fuel to satellites.

Adam Harris, Orbit Fab’s vice chairman of business development, said the corporate continues to push these projects forward with private funding but additionally relies on government support.

The corporate secured a $12 million U.S. Air Force Strategic Funding Increase — with $6 million coming from the Air Force and $6 million in matching private funds — to further develop its Rafti refueling port for compatibility with military satellites.

The Rafti port must be installed on the client satellite to be able to receive fuel. Orbit Fab is also developing a grappling device for the fuel delivery vehicle that attaches to the Rafti port.

Within the Tetra-5 experiment, a small satellite will rendezvous and dock with Orbit Fab’s depot to get hydrazine. Orbit Fab on May 25 announced it chosen Impulse Space’s orbital transfer vehicle because the hosting platform for the fuel depot. The OTV will supply power, communications, attitude control and propulsion for the fuel depot.

The military’s seemingly growing appetite for refueling capabilities is “very exciting for us,” Harris said.

“When Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman or other corporations construct spacecraft, we check with them about how you’ll be able to integrate our refueling interface in order that those spacecraft may be refillable,” he said. “We need to make that as easy as possible for all spacecraft manufacturers.”

Space Command is telling the Space Force it wants refuelable satellites by 2030. Although that seems a great distance off, planning for that future has to start out now, Harris said.

“When you realize refueling is on the market, you’ll be able to change the way in which you do business with spacecraft,” he said. “And you’ll be able to make those maneuvers without regret.”