WASHINGTON — NASA has chosen Blue Origin to develop a lunar lander to move astronauts on Artemis missions starting at the tip of the last decade.

At an event at NASA Headquarters May 19, NASA Administrator Bill Nelson announced that the agency selected a team led by Blue Origin, with participation from Boeing, Draper and Lockheed Martin, amongst others, to develop a lander called Blue Moon that may join already under development by SpaceX to move astronauts between the lunar Gateway and the surface of the moon.

The worth of the fixed-price award is $3.4 billion. John Couluris, Blue Origin program manager for the trouble, said on the briefing that the corporate plans to take a position “well north” of that quantity to develop the lander.

The contract includes an illustration landing on Artemis 5, currently scheduled for no sooner than late 2029, in addition to an uncrewed test flight of the lander about one 12 months earlier. Artemis 5 can be the third crewed landing of the Artemis lunar exploration campaign, after the Artemis 3 and 4 missions that may use SpaceX’s Starship.

Blue Origin was certainly one of two bidders, with a team led by Dynetics submitting the opposite bid. NASA officials on the briefing didn’t disclose the rationale for choosing Blue Origin over Dynetics, saying it’s going to be released in a separate source selection statement.

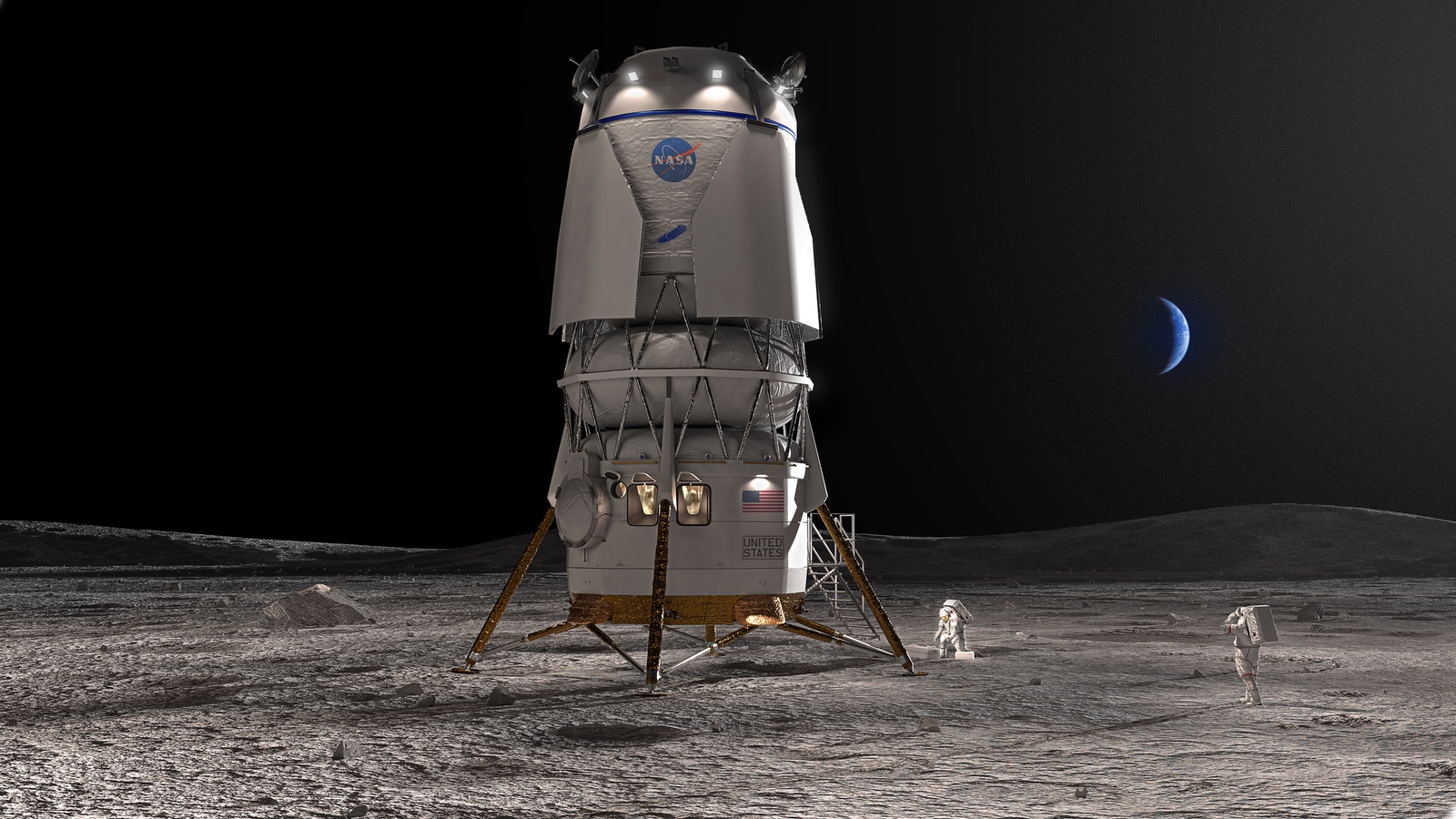

The Blue Moon lander is a revised version of earlier designs released by the corporate. The lander is 16 meters tall and designed to suit contained in the seven-meter payload fairing of Blue Origin’s Latest Glenn rocket. It has a dry mass of 16 metric tons, and greater than 45 metric tons when stuffed with liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen propellants.

Keeping those cryogenic propellants from boiling off is a key enabling technology for Blue Moon. “That is a fantastic example of the public-private partnership we’ve got with NASA,” Couluris said. The corporate has been funding internally “zero-boiloff” technology for a while, resembling a cryocooler that operates at a temperature of 20 kelvins.

“We intend to make hydrogen a storable propellant,” he said. “When you could make hydrogen storable, then you definately can do plenty of things.” That features, he said, extracting hydrogen and oxygen from lunar resources to fuel landers.

Besides the version designed to hold astronauts, Blue Origin is planning a cargo version of the lander. It should have the opportunity to move as much as 20 metric tons to the lunar surface and have the opportunity to return to lunar orbit, or 30 metric tons on one-way missions.

Blue Origin is working with Lockheed Martin, which is able to construct a “cislunar transporter” spacecraft, carrying propellant from low Earth orbit to the near-rectilinear halo orbit across the moon where the lander is positioned. That vehicle will refuel the lander, which is designed for use on multiple lander missions.

There are several other members of what Blue Origin calls its “National Team” for the lander. Draper will provide guidance, navigation and control systems in addition to training and simulation. Astrobotic will handle cargo accommodations, Honeybee Robotics will provide cargo offloading capabilities and Boeing will contribute the docking system.

“We’ve got a powerful group of very motivated, very humble yet proud people,” Couluris said, including those that worked on the corporate’s original lander proposal. “The sensation is totally incredible. I’m happy with this team, across your complete National Team.”

Path to choosing Blue Moon

NASA announced the Sustaining Lunar Development effort in March 2022 to support work on a second lander, joining SpaceX’s Starship that the agency chosen in April 2021 for its Human Landing System (HLS) program. Blue Origin and Dynetics, the 2 losing bidders in that competition, protested the award to the Government Accountability Office but had their protest rejected. Blue Origin later filed suit within the Court of Federal Claims, but lost the case.

NASA since when it announced SLD that the initiative was an effort to make sure competition in the general HLS effort, addressing concerns raised by some members of Congress. “I promised competition, so here it’s,” Nelson said on the time.

SpaceX was excluded from the SLD competition due to its existing HLS award, but NASA exercised what it called Option B in that award for a second mission that may show the greater performance required for SLD. NASA formally exercised that option in November, valued at $1.15 billion, bringing the overall value of SpaceX’s HLS work to greater than $4 billion.

After a Dec. 6 deadline for SLD proposals, each Blue Origin and Dynetics announced they were bidding. Blue Origin’s “National Team” included Lockheed Martin and Draper, who were a part of Blue Origin’s original HLS bid. Northrop Grumman, who was a part of the unique Blue Origin bid, as an alternative joined the team led by Dynetics.

Neither Blue Origin nor Dynetics disclosed details about their proposals on the time, although Dynetics released an illustration of its lander that looked much like its earlier design. Each corporations had received funding from NASA’s Next Space Technologies for Exploration Partnerships (NextSTEP) Appendix N effort in September 2021 to mature technologies resembling engines for his or her landers.

Each SpaceX’s Starship and Blue Origin’s Blue Moon will eventually compete for missions after Artemis 5 under services contracts, an arrangement much like what NASA uses for cargo and crew missions to the space station. On the announcement, Jim Free, NASA associate administrator for exploration systems development, said the agency was just starting planning for the way it’s going to acquire landers for those later missions.