Back within the Eighties, geophysicists analyzing moon rocks dropped at Earth during Apollo missions were surprised to seek out very strong magnetic fields etched onto those samples. The moon shouldn’t be large enough to power such a field, let alone accomplish that for greater than 1.5 billion years. How then, did these lunar samples get magnetized?

The conundrum had previously led a number of researchers to suspect other sources of magnetism, including the chance that the Apollo spacecraft ferrying the samples back home could also be responsible. But now, a brand new study demonstrates that the magnetization preserved in lunar rocks is, in truth, natural in origin — and that spaceflight doesn’t have a major impact on the force. These findings disprove one in all two big oppositions to the idea that the moon powered its own dynamo.

Magnetized rocks can make clear the history of planetary magnetic fields, that are crucial to guard atmospheres. Knowing such samples are usually not tarnished by spacecraft is subsequently necessary for future sample return mission planning. NASA has an ambitious endeavor to gather rock and mud samples from Mars, for example, which might be brought back to Earth for evaluation.

“You should know that the spacecraft returning your sample shouldn’t be magnetically frying your rock, essentially,” Sonia Tikoo, an assistant professor of geophysics on the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability and the lead writer of the brand new study, said in a statement.

Related: How helicopters on Mars could find hidden magnetism in planet’s crust

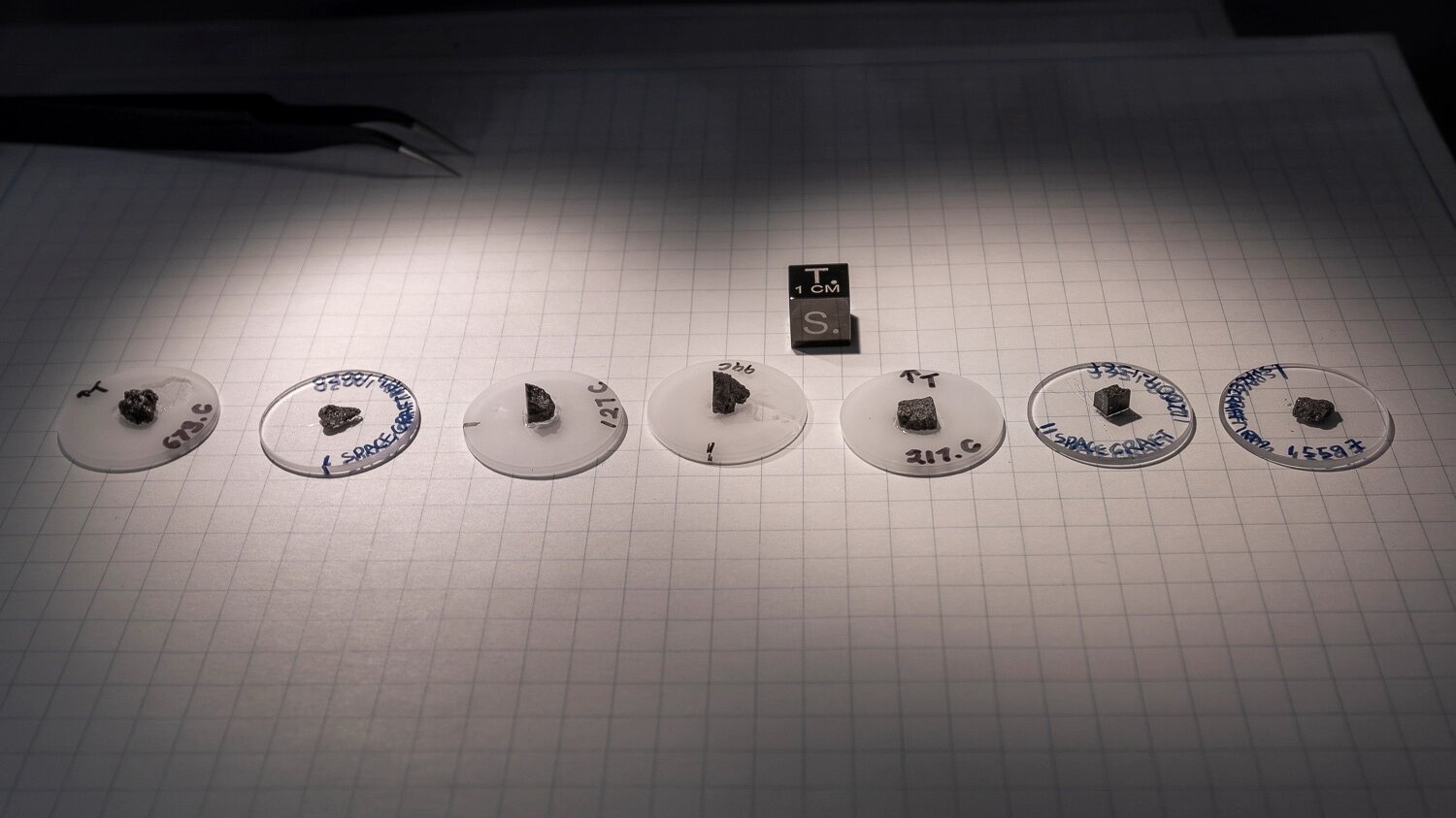

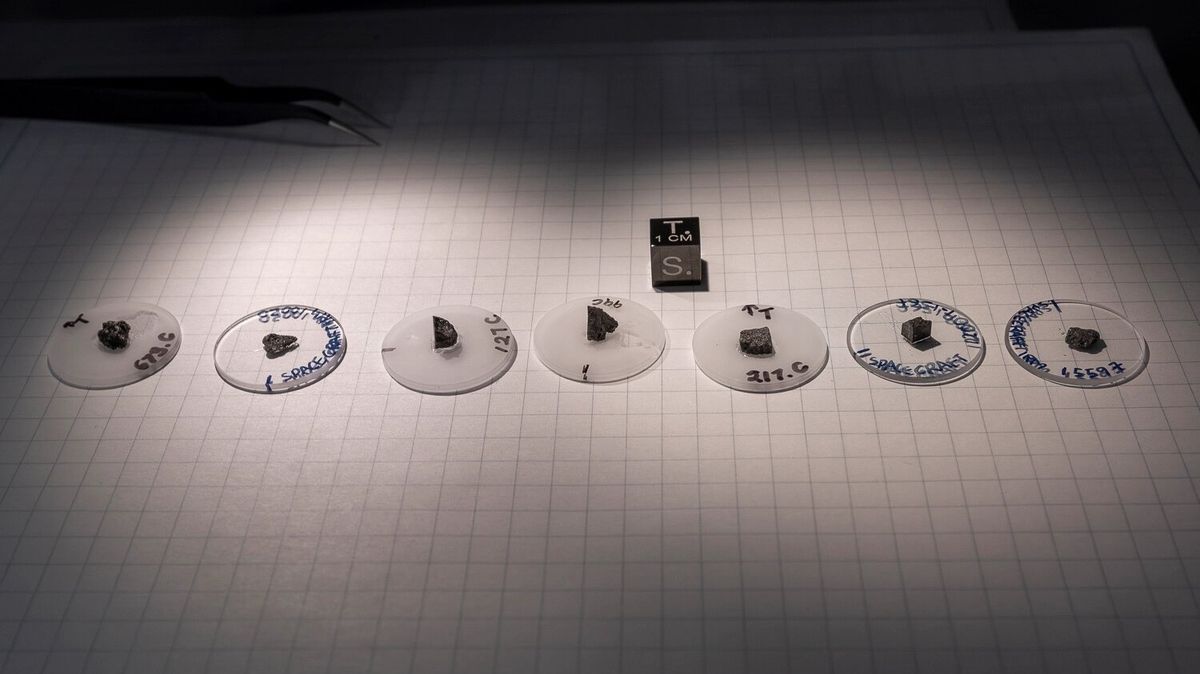

To reach at their conclusions, Tikoo and study co-author Ji-In Jung exposed eight moon rock samples from 4 Apollo missions to magnets that generated magnetic fields with strengths corresponding to those generated onboard a spacecraft. For 2 days — which replicated a return journey from the moon — the samples were specifically exposed to a field strength of 5 millitesla, which is roughly 100 times stronger than Earth’s magnetic field, based on the brand new study.

Later, the team observed how the “magnetic contamination” decayed and located it could possibly be easily cleaned using standard methods.

“This study proves that we will do extraterrestrial paleomagnetism with mission-returned samples,” Tikoo said in the identical statement. “I do not think anybody doubts the power to do Earth paleomagnetism and I’m joyful that we will do it for space, too.”

This research is described in a paper published Oct. 11 within the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/archetype/F5ERKB2GSZC7DOSER4SCJDZVSQ.jpg)